Theodore Parker's Loaded Pistol

Still a rough draft. Used in a Sunday school class, not in worship.

Among the people who used to come each Sunday to Theodore Parker's church in Boston were William and Ellen Craft. William was a carpenter, and they had a nice home in Boston, where they had lived for some years. Theodore Parker knew them well, and went often to see them in their house, and welcomed them gladly when they came to visit him. He knew the sad, true story of their past lives, which was a secret from other people in Boston: years ago they had been held as slaves by a cruel master in Georgia. They had managed to escape from slavery, and had fled over nine hundred miles, until they had finally come to safety in Boston, for Massachusetts was a free state that did not allow slavery. The Crafts lived peaceful, hard-working lives in Boston until 1850, when the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law.

The Fugitive Slave Law allowed slave owners to take former slaves who had escaped to freedom in one of the free states. To demonstrate the power of the new law, some supporters of slavery decided to pull off a high-profile capture of escaped slaves — they decided to capture William and Ellen Craft, who had been free for so long, and who lived a city which was a stronghold of abolition.

The slave-catchers came to Boston. So the Committee on Vigilance, a group of people who organized themselves to stop the Fugitive Slave Law and end slavery, went into action. Theodore Parker let Ellen hide out in his own home. By hiding Ellen, he made himself liable to a fine of a thousand dollars and imprisonment for six months under the Fugitive Slave Law. Parker said, "I will [helped a fugitive slave] as readily as I would lift a man out of the water, or pluck him from the teeth of a wolf or snatch him from the hands of a murderer. What is a fine of a thousand dollars, and gaoling for six months, to the liberty of a man? My money perish with me if it stand between me and the eternal law of God!"

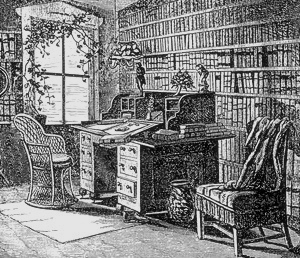

While his wife stayed in the safety of Parker's house, William Craft armed himself, and with support from the Committee on Vigilance he was able to move around Boston and keep away from the slave-catchers. Then Theodore Parker heard that the slave-catchers had threatened to break into his house at night. Determined to keep them out, Parker kept a loaded pistol at the ready. A few months later, when some other Unitarian ministers criticized Parker for breaking the law, here's what he said: "I have in my church black men [and women], fugitive slaves. They are the crown of my apostleship, the seal of my ministry. It becomes me to look after their bodies in order to 'save their souls.' This [Fugitive Slave] law has brought us into the most intimate connection with the sin of slavery. I have been obliged to take my own parishioners into my house to keep them out of the clutches of the kidnapper. Yes, gentlemen, I have been obliged to do that; and then to keep my doors guarded by day as well as by night. Yes, I have had to arm myself. I have written my sermons with a pistol in my desk,— loaded ... and ready for action. Yes, with a drawn sword within reach of my right hand. This I have done in Boston; in the middle of the nineteenth century; been obliged to do it to defend the [innocent] members of my own church, women as well as men!"

But the slave-catchers, and the Federal marshals who helped them, never broke into Parker's house. He went to their hotel, and let them know that whoever came into his house to try to capture Ellen Craft would do so at the peril of their lives. He went on to tell them exactly what the people of Boston thought of them, and what might happen to them if some people in Boston got hold of them, and Parker so scared the slave-catchers that they left the city as soon as they could catch a train out.

While all this was going on, the Committee on Vigilance — that was the name of the organization of abolitionists Parker was working with — raised enough money to send William and Ellen Craft to England, where slavery was illegal, with enough additional money so that they could get established in their new country. Before they left, it turned out that William and Ellen had never been legally married. They had been living as husband and wife when they were slaves, but since it was illegal for slaves to marry they had never married. Before they left for England, Parker officially married them. But Theodore Parker added his own twist to the marriage ceremony. Here's how he told the story:

"Then came the marriage ceremony; then a prayer such as the occasion inspired. Then I noticed a Bible lying on one table and a sword on the other. I took the Bible, put it into William's right hand, and told him the use of it. It contained the noblest truths in the possession of the human race, &c., it was an instrument he was to use to help save his own soul, and his wife's soul, and charged him to use it for its purpose, &c. I then took the sword (it was a ' Californian knife;' I never saw such a one before, and am not well skilled in such things); I put that in his right hand, and told him if the worst came to the worst to use that to save [his and] his wife's liberty, or life, if he could effect it in no other way. I told him that I hated violence, that I reverenced the sacredness of human life, and thought there was seldom a case in which it was justifiable to take it; that if he could save his wife's liberty in no other way, then this would be one of the cases, and as a minister of religion I put into his hands these two dissimilar instruments, one for the body, if need were — one for his soul at all events. Then I charged him not to use it except at the last extremity, to bear no harsh and revengeful feelings against those who once held him in bondage, or such as sought to make him and his wife slaves even now."

William and Ellen Craft succeeded in reaching England safely. This story took place in 1851, the year of the first Great Exhibition, held in London. William and Ellen appeared at the Great Exhibition, and crowds of people went to see them, two former slaves who had escaped to England, two now-free people who sang "God save the Queen" to thank Heaven for having escaped from the slave-catchers.

Sources: The Life and Writings of Theodore Parker, Albert Réville (London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Co., 1865), pp. 112-114; and The Story of Theodore Parker, Francis E. Cooke (London: Sunday School Association, 1890), pp. 100-101.